Lucky country status could soon be stress tested

Volatility has become almost synonymous with the leadership style of US President Donald Trump.

As evidenced by multiple impeachments, the Jan. 6, 2021, MAGA storm of the US Capitol and outlandish ideas of claiming Greenland and Canada as US territory, Trump’s idea of diplomacy seems to be “shoot first, justify later”.

No more is this evident in his schizophrenic global tariff regime, which saw friend and foe alike slapped with jumbo import levies in early April, followed by chaotic flip-flopping ever since.

While Australia has managed to avoid the brunt of Trump’s scattershot tariff approach with a relatively light 10% levy, the economic uncertainty that Trump is creating in his homeland nonetheless has significant implications for our domestic markets.

As it stands, the US dollar is trading near three-year lows per the US Dollar Index (DXY), while the 30-year Treasury yield, at around 5%, is near levels not seen since the Global Financial Crisis. This is unusual – historically speaking, the US dollar and US bond yields have tended to move in tandem with each other.

But just because this divergence is unusual, it doesn’t make it particularly surprising.

Treasury yields have an inverse relationship to their price, which means investors are demanding a significant premium on long-term US debt to compensate for what they see as risk to their investment.

This risk premium is understandable, given Trump’s attempted strong-arming of the US Federal Reserve into cutting rates faster and deeper, all the while sparking US inflation fears due to those pesky tariffs and a huge appetite for taking on public debt.

Devaluing the US dollar is all part of Trump’s master plan, of course. Theoretically, weakening the greenback will stimulate global demand for US goods, thus reducing the trade deficit he’s so resentful of. And if Trump is serious about onshoring US manufacturing, it appears that a cheaper US dollar is a piece of the puzzle.

Why does it matter?

There are potentially serious implications for the Australian mortgage market due to all this uncertainty.

According to Shane Oliver, chief economist at AMP Bank, the prevailing fear is that the US bond circus will have a contagious effect on Australia's bond market.

That being said, Oliver does not expect volatility to negatively influence the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)’s rate-reduction cycle. “If anything, the uncertainty coming out of the US could potentially increase the likelihood and magnitude of a rate cut,” he said.

But “it could have an impact if bond yields in the US are higher than they otherwise would have been, which could potentially mean that it pushes bond yields up in Australia as well,” Oliver added.

Upward pressure on Australian mortgages could follow as banks seek to mitigate risk. This is because higher government bond yields increase the cost of borrowing for banks. Naturally, they will pass this cost onto the customer.

All this talk of contagion risk is all contingent on the historic relationship between Australian and US bond yields applying, but there is a counterargument to be made here.

If investors are put off from investing in the US, they’ll need to divert their funds elsewhere; Australia could be a beneficiary of that.

If the Australian dollar appreciates against the greenback, “there might be a reasonable flow of money into our bonds and that would keep our yields down,” said Oliver, conceding that “it’s a bit ambiguous.”

While Oliver is not overtly worried, he conceded that an upward risk on bond yields exists. “If there is a contagion, if people start worrying about US public debt and that forces a focus on other countries’ debt, much as we saw in the eurozone crisis… that's a risk,” he said.

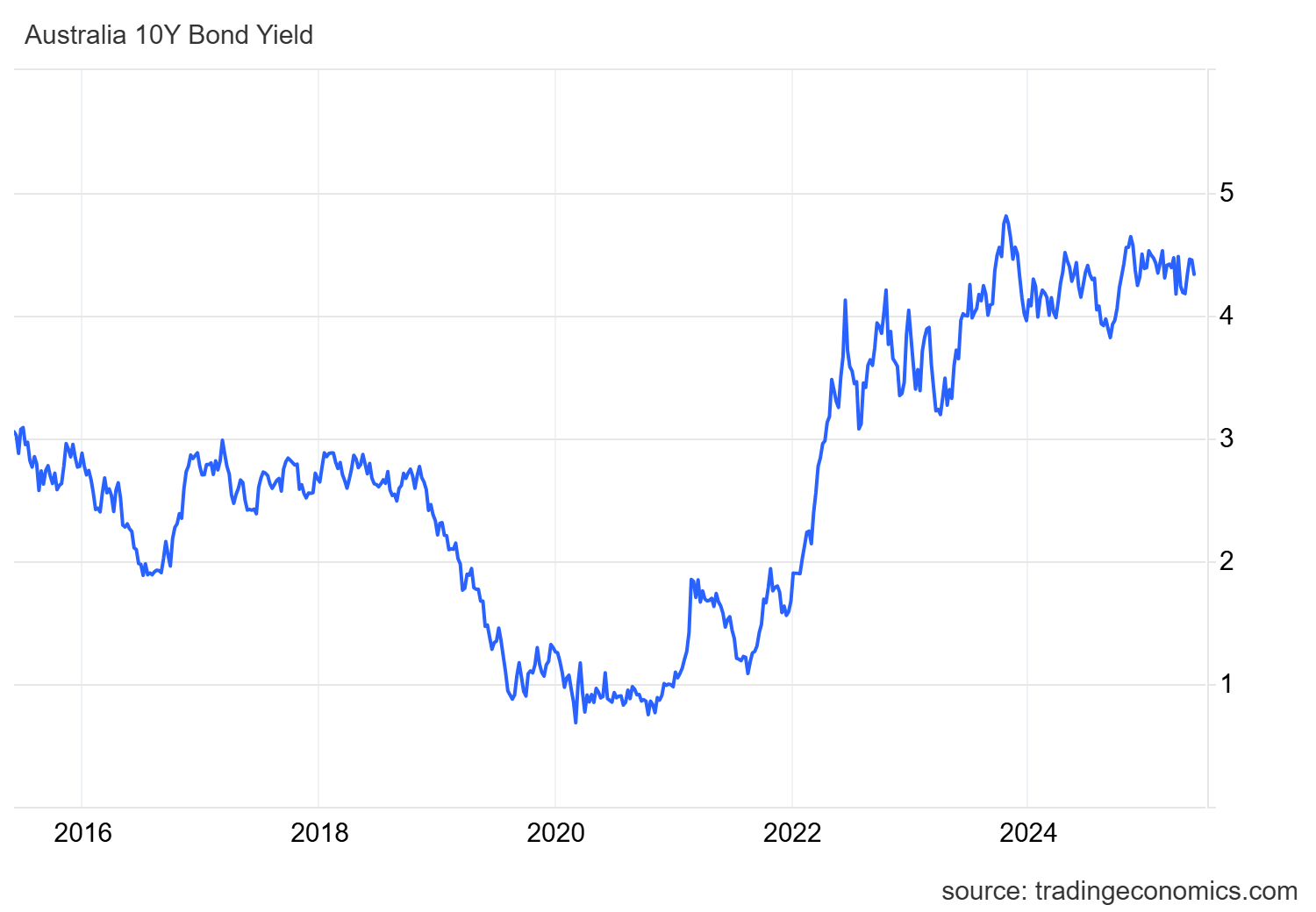

Yet here again, Australia’s status as the lucky country wins out, given its comparatively low levels of public debt. This has helped to keep Australia’s 10-year bond yield (above) below the US 10-year bond yield (below) – at 4.34% and 4.47% respectively.

To put our national debt into context, gross public debt in Australia is sitting at around 44% of gross domestic product. In the US? The figure is above 120%. Japan, meanwhile, is higher than 200%.

It is also worth noting that Australians borrow in short bursts of two to five years, making the RBA cash rate a more important benchmark for setting mortgage rates. We saw this play out last week, when most – but not all – banks acted to pass through the RBA’s 25-basis-point interest rate reduction almost immediately.

Conversely, US borrowers typically take out 30-year fixed-rate loans which tend to be benchmarked against the 30-year Treasury bond.

That bodes well for Australian borrowers in the short term, but with an erratic president in the White House and contagion an ever-present threat, the longer-term risks shouldn’t be ignored.