Adviser explains consequences of changes to investor clients

The National Party's decision to fast-track the reintroduction of interest deductibility for residential investment properties means investors will see a tax benefit sooner than anticipated.

This comes after the previous Labour government removed interest deductibility for investors, who were only able to deduct interest on newly constructed properties.

However, not all experts see it as a silver bullet for high rent and home ownership costs, with one mortgage adviser calling the policy change “progress not perfection”.

“Labour’s policy should have been scrapped straight away; however, the reality is investors will take any win here,” said Eugene Bartsaikin (pictured above), director of Twine Financial Advisers.

Twine Financial Advisers was awarded as one of the Best Mortgage Brokerage Firms in New Zealand. See the full winners here.

A recap on interest deductibility

Before 2021, investors could fully deduct the interest they paid on their mortgage from their rental income, so they only paid tax on the actual profit they made.

However, property interest limitation rules, announced by the Labour government in March 2021, effective from October that year, removed investors’ ability to offset interest paid on their mortgage against rental income for tax purposes.

Under Labour’s plan, for properties purchased before March 27, 2021, landlords could claim 50% of the interest cost in that year, reducing to 25% in April 2024 and zero deductibility available from April 1, 2025.

Investors suddenly had to pay tax on a bigger amount – even if they weren't actually making money.

This made it financially tough, especially for those who weren't making much profit to begin with.

“We can all agree that we should pay tax on the profit or income we make – however, the removal of being able to claim interest as an expense means investors needed to find money they simply didn't have,” said Bartsaikin, who was named the 2023 Adviser of the Year in the independent and franchise category.

Interest deductibility: A case study

For example, imagine an investor’s property was rented for $650/w or $33,800/a.

The investor has two expenses:

- The investor pays $30,000 per year on the mortgage.

- They also have other costs of $3,800 per year (repairs, maintenance, etc.).

If you add up the income ($33,800) and subtract the expenses ($30,000 + $3,800), you get $0. This means the investor isn't making any profit after paying the bills.

Therefore, the investor’s cash flow is $0.

“There shouldn't be any additional tax to pay as no money has been made,” said Bartsaikin.

Before 2021, the investor could deduct the mortgage interest ($30,000) from their income ($33,800). So, their taxable income for tax purposes would be nil.

However, without deductibility, the taxable income would be now $30,000 and the investor would need to find an additional $10,000/a to pay the tax.

“In reality, most investors are already subsidising their rentals and the majority of landlords in New Zealand are private mum-and-dad investors, not corporates,” Bartsaikin said.

The consequences of scrapping interest deductibility

All of this changed in October 2023, when the National Party won the national election after taking enough seats to form a coalition with Act, a natural right-wing ally.

On March 10, associate finance minister David Seymour announced the ability to deduct interest expenses will be phased back in from April 1, 2024, when all affected taxpayers will be able to claim 80% of their interest expenses and 100% from April 1, 2025, onwards.

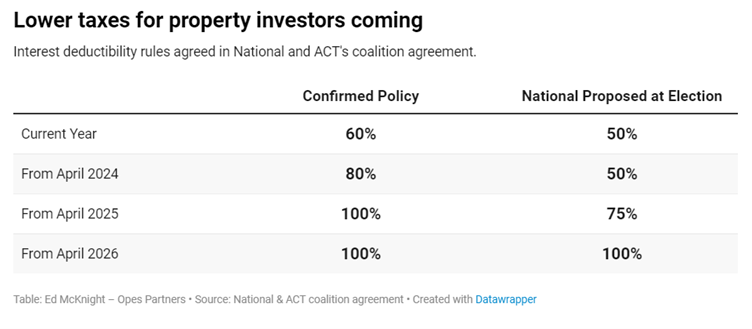

This was much faster than the initial plan, which aimed to restore a 60% deduction on rental properties in 2023/24, 80% in 2024/25, and 100% in 2025/26, which itself was faster than what was proposed at the election (see below).

Original table can be found here.

Explaining why the newly formed government accelerated the tax change, Seymour said landlords had been “hit with a double whammy” of rising mortgage interest rates and increasing interest deductibility limitations during a cost-of-living crisis.

“These costs are inevitably passed on to tenants, one of the reasons New Zealand has all-time high rental costs,” Seymour said. “This heaped pressure on landlords and renters alike by reducing the number of rentals, pushing rents up, and making it harder for Kiwis to save for their first home.”

This is the experience that Bartsaikin saw on the ground.

“What I've seen widespread is investors pushing as far as they can given market conditions to lift rents to cover the shortfall and exiting the regional market in particular due to a lack of new builds available,” he said.

“New builds are more expensive to build so all that happened was a significant shortage of rental properties everywhere except the main centres where there was no shortage of new builds.”

Was bringing back interest deductibility the right decision?

While opinions are divided, the return to the “status quo” was the right decision, according to Bartsaikin. But will it make rents go down in price? “Not exactly,” he said.

“A better tax policy overall will introduce more investors, and having more rentals on the market reduces the rate that rents can go up by and renters have more choices.”

However, he did concede that it could significantly increase confidence among investors in the market.

“Keep in mind, investors are market-takers, not makers,” Bartsaikin said. “They want to buy as cheaply as possible, so making the cash flow more viable on existing stock means they have more choices too.”

Bartsaikin suggested that this shift in investor behaviour may lead developers to rethink their profit margins if house prices remain low, thereby resulting in reduced construction activity.

Furthermore, he posits that the increased competition among developers could mitigate inflationary pressures on construction materials, contributing to a more balanced market.

Over the medium term, this could also dampen demand for new-builds, and developers may need to give up more of their margins to sell the stock as some investors end up going for existing properties.

“Less development means land values on development sites fall and the market falls into an equilibrium,” he said.

“Over the very long term we would eventually get into a shortage position again and it makes sense to build again, cycle will continue, rinse and repeat.”

What do you think about the plan to reintroduce interest deductibility for investors? Comment below.