The technology is ready, the lenders are ready – but the Australian consumer isn’t, argued delegates at the recent Australian Mortgage Innovation Summit.

The 2016 Australian Mortgage Innovation Summit, hosted by RFi Group, certainly lived up to the name – a coming together of ambitious, sharply suited bankers and brokers to discuss the bright future of the humble home loan.

Yet belying the positive mission statement, a note of frustration was also evident at this year’s summit – frustration with the slow pace of change. During a panel discussion among top bankers, as the talk inevitably drifted towards digital mortgages, a weary delegate raised his hand to ask the question: “We’ve been talking about this for six years ... why hasn’t it happened yet?”

The banks’ answer was to point towards the Australian consumer. Or, to be specific, the reality that getting a mortgage continues to be a very emotional process for borrowers, as NAB’s general manager of home lending, Meg Bonnington, pointed out in her response: “Buying a property is such an emotional thing – it’s very different to getting a credit card ... I think that’s where there’s the fallback to some sort of face-to-face.”

The banks’ answer was to point towards the Australian consumer. Or, to be specific, the reality that getting a mortgage continues to be a very emotional process for borrowers, as NAB’s general manager of home lending, Meg Bonnington, pointed out in her response: “Buying a property is such an emotional thing – it’s very different to getting a credit card ... I think that’s where there’s the fallback to some sort of face-to-face.”

Bridging that gap was the challenge, the panellists agreed. “If someone gets the end-to-end process right they’ll drive a train through my back book,” observed Westpac Group’s head of home ownership, Nathan McMullen. These major bank representatives weren’t the only speakers at the summit to cast doubt on the appeal of the digital mortgage. Pepper CEO Patrick Tuttle took an unexpected course in his opening talk on innovation: “I think the true digital online mortgage is aspirational ... it’s how you marry that with face-to-face.”

Dealing with non-vanilla mortgages added a further hurdle for Pepper, he added, concluding that a hybrid model was the future, involving both digital application portals and face-to-face advice.

Tuttle’s conclusion was surprising, to say the least, for a conference largely focused on digital innovation. It also begged the question: after years of eagerly anticipating the fully digitised mortgage, why had lenders suddenly cooled on the idea? And – the elephant in the room – will brokers have a place in the worlds of either hybrid or complete digital mortgages? MPA set out to find the answers.

The technology is here

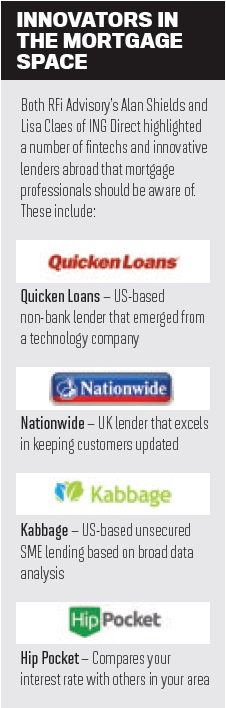

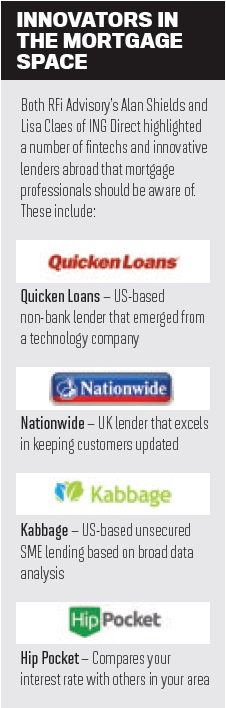

One thing made very clear across the summit was that both the technology and the business models to make digital mortgages viable did exist. One company looms large in lenders’ minds here: Quicken Loans in the US, whose Rocket Mortgage product can be applied for on a mobile app, as its glossy advert during the recent Super Bowl made clear, with its message of ‘push a button, get a mortgage’. Tuttle picked out Quicken as an innovator, as did ING Direct’s Lisa Claes in her talk on marketing in the digital age.

Quicken is a huge player, and one of the biggest mortgage originators in the US, but brokers should also be aware of the numerous smaller fintech companies jumping ahead of established Australian lenders in developing digital lending tools. For example, start-up Hip Pocket, which doesn’t yet operate in Australia, uses social media to compare your mortgage repayments with those of similar people in your area, with exciting prospects for refinancing, explained Claes.

Encouragingly, brokers themselves are also pushing the boundaries of digital lending. In a panel discussing white label and third-party branding, Connective director Mark Haron noted that one of the aggregator’s biggest brokerages had actually developed a fully digitised application procedure but none of the banks had signed up to it. Nevertheless, Haron added, he couldn’t see any major changes in the consumer psyche over the next two years – a message delegates heard again and again across the two-day summit.

Consumers and the digital mortgage

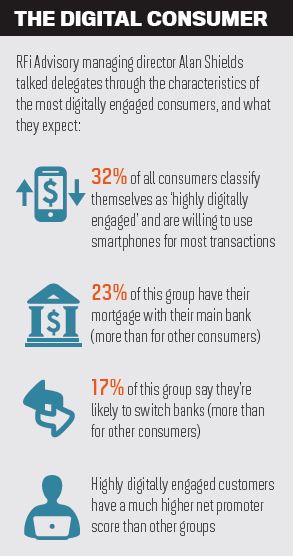

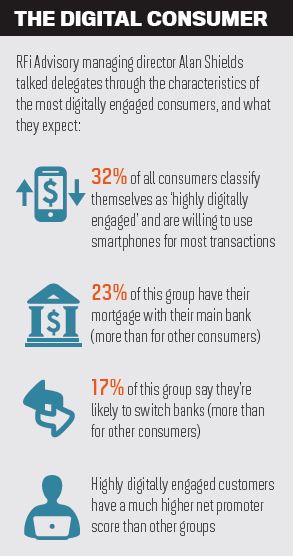

Lenders, it seems, don’t believe the consumer demand exists yet. “Every time we go into a focus group with a customer, you’re sitting there, waiting for them to say, ‘I’d just love it if I could do the whole thing digitally’,” noted Westpac’s McMullen. “Unfortunately there isn’t many of them.” The bankers were echoing a point made by RFi Advisory managing director Alan Shields, who reported that 68% of surveyed consumers said they wouldn’t do any part of their mortgage application online.

It’s not Australia’s pensioners holding back the fully digital mortgage, speakers suggested; the demand for face-to-face support actually came from highly digitally literate younger borrowers. Shields said buyers under the age of 30 were prepared to sacrifice a couple of basis points in exchange for better support, telling delegates that “digital engagement and price sensitivity is not binary”.

Furthermore, when MPA asked Shields if younger, more digitally engaged buyers were likely to use a broker, he replied that first home buyers were still more likely to use a broker to help them with the application. Conversely, this could mean older upgraders and refinancers could be the first adopters of digital mortgages as they’re more comfortable with the transaction, explained Brad Gravell, general manager of home loans and pricing at ANZ.

“We will get to a point where the systems are capable of self-serve,” Gravell explained. “But I think the main game over the next few years will be assisted self-service.”

Assisted self-service (or as Tuttle called it, a hybrid mortgage) – with a banker or broker on hand to assist – was a running theme of the summit. Even UBank, the NAB-owned online mortgage pioneer, was moving towards what head of digital Jeremy Hubbard called “digital mainly”, allowing customers to opt in and opt out of the online process in an omnichannel approach.

Brokers and the digital mortgage

Brokers and the digital mortgage

By its very definition, the end-to-end digital mortgage seems to spell bad news for brokers. The assisted self-service mortgage, on the other hand, could be a considerable opportunity for brokers, speakers at the summit explained.

“It seems to me in the discussions today that the importance of personal service has been discarded,” commented Randall Williams, senior vice president at La Trobe Financial. In common with other non-bank lenders at the conference, Williams explained the importance of brokers in dealing with specialist borrowers whose applications could not easily be replicated online.

Mark Hewitt, AFG’s general manager, suggested that the proliferation of online mortgage options had actually driven more confused customers to brokers for a simple explanation. When MPA asked him what this meant for brokers’ marketing strategies, Hewitt did, however, warn that brokers couldn’t just sit back and wait for these confused customers to arrive. As for lenders, he added, they should look at the relatively low conversion rate of online-generated leads compared to those that come through brokers – as he put it, “the best conversion is still from the customer you looked after”.

In practical terms, assisted digitisation that includes brokers has a number of advantages, lenders told the summit. Electronic verification of identity alone saved ING Direct a ‘double-digit percentage’ in back-office costs, recalled customer delivery executive Claes. Improvements in the broker and digital channels can intersect, argued John Arnott, ING Direct’s executive director of customers. “It’s around turnaround times; how you get a faster yes or a faster no,” he said. Giving brokers the digital tools to easily show customers their different options could provide brokers with another advantage, he added: “The customer ultimately feels they’re getting better value from the broker.”

Beyond traditional relationship management, brokers could play a crucial role in satisfying millennial consumers’ growing expectations. In her talk on changing demands, ING Direct’s Claes suggested lenders should “become this butler in your customer’s life to provide for their broader needs”. And brokers may need to move in a similar direction, speakers noted. YBR Wealth Management CEO Matt Lawler warned brokers that “we’ve got to make sure our proposition to the client is more than helping them with their mortgage transaction; we’ve got to help them to a better financial future”.

Will brokers be left out in the cold?

While speakers believed the assisted digital mortgage could work for brokers, this depends on whether brokers are being written into, or out of, that process. Digital pioneers like UBank don’t use the broker channel, instead providing their own support, and lenders – perhaps understandably – are prioritising their organic channels for digitisation before their broker channel.

MPA asked Samantha Hellen, head of strategy and service quality, home ownership, at Westpac Group, whether the group’s banks were coordinating the development of digital channels with its third-party distribution. “We’re in pretty early days; we’re a big beast across many brands,” she replied, noting that St.George was perhaps furthest ahead in combining the two. As for the major bank, “[a] Westpac brand [digital application] for brokers is absolutely on the cards and absolutely on the to-do list in the near future, but we haven’t embarked on that process yet”.

The final conference of the day – on business innovation in the third-party channel – largely affirmed the ongoing role of brokers, with Home Loan Experts’ managing director Otto Dargan telling delegates about how his brokerage was responding to digitisation.

A note of warning was sounded, however, by Miki Lee, founder of broker comparison site Flongle. She predicted “the intermediary sector will come under increasing margin pressure” because digitisation of customer data would enable competitors to challenge the broker proposition.

Sites like Flongle also offered assisted digital mortgages through their own staff, she explained, but unlike brokers did so at a much lower cost, thanks to digitised processes. Furthermore, their fee-for-service model meant that all commission payments could be handed on to consumers as discounts. With an average LVR of 68% and loan size of $700,000, Lee insisted that this model of comparison site was finding favour with prime borrowers. Digital mortgages would force change in the broker channel, she concluded: “That’s the more important question: ‘what is the broker?’ rather than ‘will the broker survive?’”

The state of play

So, how far are we from the digital mortgage? By the end of the two-day Australian Mortgage Innovation Summit, hundreds of delegates and over 20 talks and panels had pondered this question and produced a number of predictions. Clearly, the fully digital mortgage for vanilla loans is technically possible, as it is already being done abroad – not only by Quicken in the US but also in Europe, particularly Spain.

“The tools are on our fingertips,” noted ING Direct’s Claes. While this process has been delayed by legislation in Australia, the role of paper and wet signatures in the application process is gradually being reduced, argued Mike Cameron, group executive of operations at PEXA. “We’re talking about changing 150 years of ‘this is the way it’s done’… [but] the heavy lifting has been done,” he said.

Despite these considerable advances, the Australian consumer remains unwilling to part with the human element of what continues to be an emotional transaction, almost all lenders present agreed. Counterintuitively, it appears those younger buyers who are most digitally engaged are also less comfortable with the mortgage transaction, making brokers – or at least some model of adviser – a continuing necessity, and indeed these consumers appear to be prepared to pay extra for more support. Many speakers suggested that brokers could provide this support, but of course whether banks will involve them in the assisted self-serve mortgage application process remains open to question.

Of all the points made by speakers during the summit, one of the most surprising was not about technology at all. The digital mortgage, argued RFi Advisory’s Shields, should not just be a digitised version of the current mortgage application, a confusing process for borrowers which has only got more complicated with increasing regulation, playing a part in the rise of the broker channel with its proposition of impartial advice. Instead, the digital mortgage should use data to reduce the amount of information the customer needs to provide, argued Shields: “Imagine if you had a friend for 10 years and every time you met they asked your name; it wouldn’t be a good experience.”

Perhaps, as Shields suggests, when it comes to digital mortgages consumers’ problems are less with the ‘digital’ part and more with the mortgage itself.

Yet belying the positive mission statement, a note of frustration was also evident at this year’s summit – frustration with the slow pace of change. During a panel discussion among top bankers, as the talk inevitably drifted towards digital mortgages, a weary delegate raised his hand to ask the question: “We’ve been talking about this for six years ... why hasn’t it happened yet?”

The banks’ answer was to point towards the Australian consumer. Or, to be specific, the reality that getting a mortgage continues to be a very emotional process for borrowers, as NAB’s general manager of home lending, Meg Bonnington, pointed out in her response: “Buying a property is such an emotional thing – it’s very different to getting a credit card ... I think that’s where there’s the fallback to some sort of face-to-face.”

The banks’ answer was to point towards the Australian consumer. Or, to be specific, the reality that getting a mortgage continues to be a very emotional process for borrowers, as NAB’s general manager of home lending, Meg Bonnington, pointed out in her response: “Buying a property is such an emotional thing – it’s very different to getting a credit card ... I think that’s where there’s the fallback to some sort of face-to-face.”Bridging that gap was the challenge, the panellists agreed. “If someone gets the end-to-end process right they’ll drive a train through my back book,” observed Westpac Group’s head of home ownership, Nathan McMullen. These major bank representatives weren’t the only speakers at the summit to cast doubt on the appeal of the digital mortgage. Pepper CEO Patrick Tuttle took an unexpected course in his opening talk on innovation: “I think the true digital online mortgage is aspirational ... it’s how you marry that with face-to-face.”

Dealing with non-vanilla mortgages added a further hurdle for Pepper, he added, concluding that a hybrid model was the future, involving both digital application portals and face-to-face advice.

Tuttle’s conclusion was surprising, to say the least, for a conference largely focused on digital innovation. It also begged the question: after years of eagerly anticipating the fully digitised mortgage, why had lenders suddenly cooled on the idea? And – the elephant in the room – will brokers have a place in the worlds of either hybrid or complete digital mortgages? MPA set out to find the answers.

The technology is here

One thing made very clear across the summit was that both the technology and the business models to make digital mortgages viable did exist. One company looms large in lenders’ minds here: Quicken Loans in the US, whose Rocket Mortgage product can be applied for on a mobile app, as its glossy advert during the recent Super Bowl made clear, with its message of ‘push a button, get a mortgage’. Tuttle picked out Quicken as an innovator, as did ING Direct’s Lisa Claes in her talk on marketing in the digital age.

Quicken is a huge player, and one of the biggest mortgage originators in the US, but brokers should also be aware of the numerous smaller fintech companies jumping ahead of established Australian lenders in developing digital lending tools. For example, start-up Hip Pocket, which doesn’t yet operate in Australia, uses social media to compare your mortgage repayments with those of similar people in your area, with exciting prospects for refinancing, explained Claes.

Encouragingly, brokers themselves are also pushing the boundaries of digital lending. In a panel discussing white label and third-party branding, Connective director Mark Haron noted that one of the aggregator’s biggest brokerages had actually developed a fully digitised application procedure but none of the banks had signed up to it. Nevertheless, Haron added, he couldn’t see any major changes in the consumer psyche over the next two years – a message delegates heard again and again across the two-day summit.

Consumers and the digital mortgage

Lenders, it seems, don’t believe the consumer demand exists yet. “Every time we go into a focus group with a customer, you’re sitting there, waiting for them to say, ‘I’d just love it if I could do the whole thing digitally’,” noted Westpac’s McMullen. “Unfortunately there isn’t many of them.” The bankers were echoing a point made by RFi Advisory managing director Alan Shields, who reported that 68% of surveyed consumers said they wouldn’t do any part of their mortgage application online.

It’s not Australia’s pensioners holding back the fully digital mortgage, speakers suggested; the demand for face-to-face support actually came from highly digitally literate younger borrowers. Shields said buyers under the age of 30 were prepared to sacrifice a couple of basis points in exchange for better support, telling delegates that “digital engagement and price sensitivity is not binary”.

Furthermore, when MPA asked Shields if younger, more digitally engaged buyers were likely to use a broker, he replied that first home buyers were still more likely to use a broker to help them with the application. Conversely, this could mean older upgraders and refinancers could be the first adopters of digital mortgages as they’re more comfortable with the transaction, explained Brad Gravell, general manager of home loans and pricing at ANZ.

“We will get to a point where the systems are capable of self-serve,” Gravell explained. “But I think the main game over the next few years will be assisted self-service.”

Assisted self-service (or as Tuttle called it, a hybrid mortgage) – with a banker or broker on hand to assist – was a running theme of the summit. Even UBank, the NAB-owned online mortgage pioneer, was moving towards what head of digital Jeremy Hubbard called “digital mainly”, allowing customers to opt in and opt out of the online process in an omnichannel approach.

Brokers and the digital mortgage

Brokers and the digital mortgageBy its very definition, the end-to-end digital mortgage seems to spell bad news for brokers. The assisted self-service mortgage, on the other hand, could be a considerable opportunity for brokers, speakers at the summit explained.

“It seems to me in the discussions today that the importance of personal service has been discarded,” commented Randall Williams, senior vice president at La Trobe Financial. In common with other non-bank lenders at the conference, Williams explained the importance of brokers in dealing with specialist borrowers whose applications could not easily be replicated online.

Mark Hewitt, AFG’s general manager, suggested that the proliferation of online mortgage options had actually driven more confused customers to brokers for a simple explanation. When MPA asked him what this meant for brokers’ marketing strategies, Hewitt did, however, warn that brokers couldn’t just sit back and wait for these confused customers to arrive. As for lenders, he added, they should look at the relatively low conversion rate of online-generated leads compared to those that come through brokers – as he put it, “the best conversion is still from the customer you looked after”.

In practical terms, assisted digitisation that includes brokers has a number of advantages, lenders told the summit. Electronic verification of identity alone saved ING Direct a ‘double-digit percentage’ in back-office costs, recalled customer delivery executive Claes. Improvements in the broker and digital channels can intersect, argued John Arnott, ING Direct’s executive director of customers. “It’s around turnaround times; how you get a faster yes or a faster no,” he said. Giving brokers the digital tools to easily show customers their different options could provide brokers with another advantage, he added: “The customer ultimately feels they’re getting better value from the broker.”

Beyond traditional relationship management, brokers could play a crucial role in satisfying millennial consumers’ growing expectations. In her talk on changing demands, ING Direct’s Claes suggested lenders should “become this butler in your customer’s life to provide for their broader needs”. And brokers may need to move in a similar direction, speakers noted. YBR Wealth Management CEO Matt Lawler warned brokers that “we’ve got to make sure our proposition to the client is more than helping them with their mortgage transaction; we’ve got to help them to a better financial future”.

Will brokers be left out in the cold?

While speakers believed the assisted digital mortgage could work for brokers, this depends on whether brokers are being written into, or out of, that process. Digital pioneers like UBank don’t use the broker channel, instead providing their own support, and lenders – perhaps understandably – are prioritising their organic channels for digitisation before their broker channel.

MPA asked Samantha Hellen, head of strategy and service quality, home ownership, at Westpac Group, whether the group’s banks were coordinating the development of digital channels with its third-party distribution. “We’re in pretty early days; we’re a big beast across many brands,” she replied, noting that St.George was perhaps furthest ahead in combining the two. As for the major bank, “[a] Westpac brand [digital application] for brokers is absolutely on the cards and absolutely on the to-do list in the near future, but we haven’t embarked on that process yet”.

The final conference of the day – on business innovation in the third-party channel – largely affirmed the ongoing role of brokers, with Home Loan Experts’ managing director Otto Dargan telling delegates about how his brokerage was responding to digitisation.

A note of warning was sounded, however, by Miki Lee, founder of broker comparison site Flongle. She predicted “the intermediary sector will come under increasing margin pressure” because digitisation of customer data would enable competitors to challenge the broker proposition.

Sites like Flongle also offered assisted digital mortgages through their own staff, she explained, but unlike brokers did so at a much lower cost, thanks to digitised processes. Furthermore, their fee-for-service model meant that all commission payments could be handed on to consumers as discounts. With an average LVR of 68% and loan size of $700,000, Lee insisted that this model of comparison site was finding favour with prime borrowers. Digital mortgages would force change in the broker channel, she concluded: “That’s the more important question: ‘what is the broker?’ rather than ‘will the broker survive?’”

The state of play

So, how far are we from the digital mortgage? By the end of the two-day Australian Mortgage Innovation Summit, hundreds of delegates and over 20 talks and panels had pondered this question and produced a number of predictions. Clearly, the fully digital mortgage for vanilla loans is technically possible, as it is already being done abroad – not only by Quicken in the US but also in Europe, particularly Spain.

“The tools are on our fingertips,” noted ING Direct’s Claes. While this process has been delayed by legislation in Australia, the role of paper and wet signatures in the application process is gradually being reduced, argued Mike Cameron, group executive of operations at PEXA. “We’re talking about changing 150 years of ‘this is the way it’s done’… [but] the heavy lifting has been done,” he said.

Despite these considerable advances, the Australian consumer remains unwilling to part with the human element of what continues to be an emotional transaction, almost all lenders present agreed. Counterintuitively, it appears those younger buyers who are most digitally engaged are also less comfortable with the mortgage transaction, making brokers – or at least some model of adviser – a continuing necessity, and indeed these consumers appear to be prepared to pay extra for more support. Many speakers suggested that brokers could provide this support, but of course whether banks will involve them in the assisted self-serve mortgage application process remains open to question.

Of all the points made by speakers during the summit, one of the most surprising was not about technology at all. The digital mortgage, argued RFi Advisory’s Shields, should not just be a digitised version of the current mortgage application, a confusing process for borrowers which has only got more complicated with increasing regulation, playing a part in the rise of the broker channel with its proposition of impartial advice. Instead, the digital mortgage should use data to reduce the amount of information the customer needs to provide, argued Shields: “Imagine if you had a friend for 10 years and every time you met they asked your name; it wouldn’t be a good experience.”

Perhaps, as Shields suggests, when it comes to digital mortgages consumers’ problems are less with the ‘digital’ part and more with the mortgage itself.